Book review : Dalvir S. Pannu, The Sikh Heritage: Beyond Borders

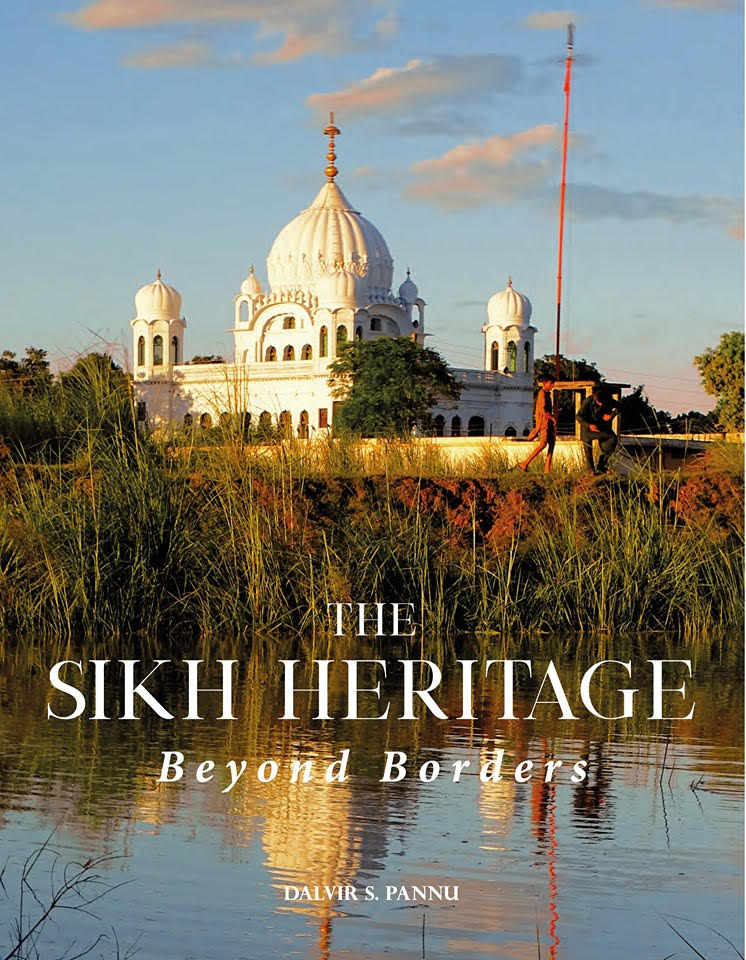

On the occasion of releasing his book, ‘We the Sikhs’, in 2019, Kapil Dev, the legendary cricketer, explained how he came to write the book. It began, he said, when he visited a gurudwara in Pakistan and got so moved. Any follower of Guru Nanak would have similar feelings seeing the gurudwaras Dalvir S. Pannu has written about. Guru Nanak and the successor Gurus’ teachings are universal. Like the Gurus’ teachings, the gurudwaras are for everyone. Mr Pannu’s, ‘The Sikh Heritage: Beyond Borders’ should be of interest to everyone interested in our common heritage. Borders are irrelevant where heritage is concerned. This book suggests the urgent need for the Sikh heritage to be made accessible to the world, beginning in the subcontinent. It is here that political borders need to urgently give way to greater accessibility so that a shared heritage can help foster the peace and healing to which the Gurus gave their lives. Mr Pannu’s book comes at a moment when the opening by Pakistani and Indian authorities of the Kartarpur Corridor offers a hopeful signal of the immense potential and opportunity for both countries to sustain and strengthen the relevance of these teachings to our times. Facilitating such access and inspiration is the management challenge which these pages suggest. The documentation, conservation and protection of sites sacred to Sikhism through joint effort in India and Pakistan can bring together the tangible and intangible dimensions of a heritage of extraordinary power and richness. Together they offer a spiritual and cultural ecology that has global significance.

Mr Pannu’s book is the latest on the gurudwaras and the Sikh heritage in Pakistan. The first book on the gurudwaras in Pakistan that I read in the early 1970s was published by some official body of Pakistan. It listed the gurudwaras with their brief description and some black and white photographs. Books by Indian writers, Hari Singh, Mohinder Singh and others, some of them in Punjabi, came out later. Then came two sumptuously produced coffee-table volumes by Amardeep Singh ‘Lost Heritage: The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan’ in 2016 and ‘The Quest Continues: Lost Heritage – The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan’ in 2018. In Pakistan, a coffee-table book was brought out written by Dr Safdar Ali Shah with photographs by Syed Javaid Kazi, the renowned photographer and president of the Photographic Society of Pakistan. Iqbal Qaiser wrote ‘Historical Sikh Shrines in Pakistan’. The Archaeology Department of Pakistan published ‘Sikh Shrines in Pakistan’ by Khan Mohammed Waliullah. Samia Karamat, one of the eminent architects of Pakistan and a professor of architecture, wrote ‘Architecture of Sikh Shrines and Gurudwaras in Pakistan’. These materials were available to Mr Pannu and are noted in his bibliography.

When so many writers write on the same subject, what distinguishes one work from another can be the approach of the author. Ms Karamat focuses on the architecture of the gurudwaras, describing how it evolved and reflected the tenets of the faith. Mr Waliullah said that his purpose was to write a book which pilgrims and visitors could take back with them as a souvenir. Mr Safdar Ali Shah and Mr Kazi wanted to ‘showcase the fact that in Pakistan holy places of minorities are well looked after’. (In line with this were similar books on the heritage of Hindus and Christians in Pakistan.) Mr Amardeep Singh’s two volumes are a quest for tracing a lost heritage and discovering his ancestral roots. Mr Pannu’s approach is academic. He has studied his subject deeply, with an historian’s rigour: ‘I get the feeling that I can almost talk to these buildings and even listen to them. Each individual structure has a unique past and a story to tell’, writes Mr Pannu. He has told some of those stories in this book and starts by narrating how the shared heritage became ‘the lost heritage’. The story of partition of India is told briefly. He quotes Leonard Mosely:

India in 1947 was a bumper year for vultures. They had no need to look for rotting flesh for it was all around them, animal and human … 600,000 dead. 14,000,000 driven from their homes. 100,000 young girls kidnapped by both sides, forcibly converted or sold on the auction block.

In Punjab, they say it was not the partition of India but the partition of Punjab and Bengal, and in Punjab the partition of Majha, the region where the Sikh faith grew. Rediscovering the common heritage after all these years is perhaps part of a healing process.

‘The Sikh Heritage: Beyond Borders’ is indeed a coffee-table book yet a scholarly work. It is not easy for a Sikh to write on the subject of gurudwaras left in Pakistan dispassionately, for Ardas, the Sikhs’ formal prayer recited morning and evening everyday includes these words: ‘Grant us the gift of serving and taking care of the gurudwaras and holy places we have been separated from’. When the Kartarpur Corridor was inaugurated in 2019 on the occasion of the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak, enabling entry to Indian pilgrims, Sikhs believed that it was the beginning of their prayers being answered. Mr Pannu writes objectively. He has read most of the literature about the Sikhs, their traditions and gurudwaras. There is a lengthy bibliography at the end of the book. His objective approach also allows Mr Pannu to touch upon some controversies such as the date of birth of Guru Nanak and the existence of Bhai Bala, the companion of Guru Nanak. About the former Mr Pannu writes: ‘In the Sikh hagiographic literature, there is univocal agreement on the birth year of Guru Nanak; however, there is disparity over the birth month in several traditions. ‘Bala Janamsakhi Mahima Prakash Kavita’ (1776) and ‘Sri Guru Nanak Prakash’ (1823) record the birth of Guru Nanak in the month of ‘Kattak’ (October–November). In contra point to that according to ‘Meharban Janamsakhi’, ‘Puratan Janamsakhi’ and ‘Bhai Mani Singh Janamsakhi’, Guru Nanak was born in the month of Vaisakh (April–May). This is the Kattak or Vaisakh controversy of some historians. However, for most ordinary Sikhs, Guru Nanak was born in the month of Kartik (Kattak in Punjabi), and they celebrate his birthday on Kartik Poornima. About Bhai Bala, Mr Pannu writes: ‘Many historians nowadays believe that not only the “Bala Janamsakhi” is counterfeit, but “Bala Sandhu” is also a fictitious character who served the narrator’s agenda when he crafted a biography of Guru Nanak’. Sikhs dismiss these ‘historians’ Mr Pannu refers to. Above the door of Sri Harmandir Sahib, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, is a golden relief showing Guru Nanak flanked by Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana. Bhai Bala is an inseparable part of the iconography of Guru Nanak. He is a part of the Sikh collective consciousness. One of the greatest Punjabi poets, Harinder Singh Mahboob, who was also a profound scholar of Sikhism, has forcefully demolished these two theories. Mr Pannu has reproduced the picture of Guru Nanak with Bhai Mardana and Bhai Bala, his two companions (p. 63), a popular print. Bhai Mardana was a Muslim and Bhai Bala was a Hindu. This iconographic representation of Sikh, Hindu and Muslim harmony captures the essence of Sikhism.

A problem with Mr Pannu’s objective approach is how to deal with miraculous incidents associated with many gurudwaras. For the ordinary Sikhs, that is not a problem. They accept devoutly what the Janamsakhis say. Historians—and Mr Pannu—call the Janamsakhis hagiographical accounts. Ordinary Sikhs understand that Sakhi is derivation (tadbhava) of Sakshi, an eyewitness account. Mr Pannu writes:

A popular “Sakhi” relates that one warm afternoon, while grazing his father’s cattle, Guru Nanak lay down under the shade of a tree to relax. In the evening, Rai Bular passed by and Guru Nanak was deep asleep. Miraculously, the tree’s shadow had not moved since midday, though the other shadows had shifted as the sun moved across the sky.

There is a gurudwara commemorating this miracle. So Mr Pannu has to mention it. But then he says, ‘Long before the origin of Sikhism, such miracles have been considered outward signs of a person possessing prophetic tendencies…’. Mr Pannu admits that his is a ‘sincere attempt to incorporate logic and rationality’ in the interpretation of Sikh traditions. Rationality and faith make uneasy companions.

A reader not familiar with the history and culture of the Sikhs will get a good idea of both from this book. It would help them understand to some extent a vital community of India and why it has always been at the forefront of fighting injustice and tyranny right up to the Kisan Andolan, a community of ‘Andolan Jeevis’. Some of the information gathered by Mr Pannu would be new to many Sikhs as well, such as that about Suthra Shah and Jhingar Shah. Mr Pannu has brought to light a little known fact about Suthreshahis, that they built their centres in Jaunpur and southern India and even Qandahar. Such nuggets of information make Mr Pannu’s work valuable. Suthra Shah, brought up by Guru Hargobind Sahib, was a very humorous person, and his poetry in Punjabi is also humorous: ‘To the beat of drums the house was looted. And the people called it wedding.’ Understandably, Mr Pannu’s work is more about the tangible heritage; the intangible heritage of poetry, music, painting, folklore and legends deserves another book from him.

Most of the major shrines have been described in detail by Mr Pannu. From Gurudwara Janam Asthan at Nankana Sahib, the birthplace of Guru Nanak, to Gurudwara Darbar Sahib at Kartarpur, the last resting place of Guru Nanak, the book covers the saga of the Sikh faith across the region that is now Pakistan. No one can remain unmoved on visiting the Kartarpur Sahib Gurudwara. Mr Pannu quotes a pilgrim who visited Kartarpur in 1647 and recorded that ‘there was mari (funeral shrine), and by the side of the mari, was his tomb (mazar)’. Mr Pannu does not dwell on this. Sikhs believe that when Guru Nanak breathed his last, a dispute started between his Hindu followers and Muslim followers. The Hindus wanted to cremate him and the Muslims to bury him. When they lifted the sheet, they found only flowers. Hindus cremated half the flowers and Muslims buried the other half. On the cremation site is the Gurudwara and side by side is the grave. An old saying is, ‘Nanak Shah Fakeer, Hindu ka Guru Musalman ka Peer’.

Guru Nanak is the path to peace in the subcontinent. The great Punjabi poet Puran Singh wrote, ‘Punjab Jeenda Guran de nam te’—Punjab lives by the name of Gurus. Mr Pannu’s book will be a standard work of reference on the subject. It is a welcome addition to the literature on gurudwaras. Mr Pannu should be congratulated for a work of outstanding quality. This book should be translated into Punjabi. It would be popular at the Singhu Border, now so much in the news.